“Everyone is unhappy in their marriages,” a divorced friend once told me. “You just don’t realize it until you’re divorced, and then other divorced people finally tell you the truth.”

I told her I was happy in my marriage. “You and Bill are different. Most husbands aren’t like Bill.” I told her that most of the couples I knew seemed pretty happy in their marriages. “That’s what they tell you,” she said.

But the married couples I knew didn’t sugarcoat things. They were extremely open about their frustrations and disappointments with each other. We’d sit around griping about how irritating our spouses were, and then our spouses would enter the room and we’d say it to their faces and we’d all laugh. For as little as you can discern about a marriage from the outside looking in, my married friends seemed satisfied — or at least satisfied enough to be cheerful and honest about their frustrations.

These two extremes — the idea that married people are mostly miserable but don’t talk about it, and the idea that married people are mostly happy and their complaints are just the noise you make when you’re married — were so at odds with each other, it hinted that there was something a little off about the way we talk about marriage in public, in writing, at parties and even privately, directly to each other. And the more I discussed marriage with my closest friends and with readers of my advice column Ask Polly, the more I encountered the fear that if you say anything negative about your spouse, people will assume that you’re deeply unhappy and your marriage is doomed.

For a while, I waved these fears off as irrational, assuming most people understand that even great marriages have their ups and downs. But I encountered similar fault lines in the books I read about marriage: From the first chapter to the last, the author mentions that her husband is the best man she’s ever known so often that it’s unsettling. Even if that is true, where’s the drama? Can’t you dig up a few bad moments, if only to build some suspense? It’s as if the author assumes that the slightest fissure will call her true love into question. Meanwhile, memoirs of divorce tend to serve up merciless portraits of exes and of marriage in general.

And then there’s this burgeoning faction of online pundits whose marriages and partnerships and relationships are happy — truly so very happy and content, they are just so lucky, they are so unmatched in their deeply egalitarian and communicative ways! Somehow, though, such writers almost uniformly suspect that most other people are absolutely miserable in their marriages. These writers look down from their perfect unions, at the so-called feminist victims of compromised, dissatisfying pairings, and shake their heads at how unenlightened and trapped these women are, shrugging off conflict that’s surely abusive, tolerating unequal separation of domestic tasks that’s almost certainly a manipulation, one spouse malevolently and selfishly asserting their needs while the other spouse suffers.

Such assessments strike me as not just myopic but wildly uncharitable to the vast majority of real-life marriages. It’s one thing to state unequivocally that domestic abuse and violence remains a big problem in our country. It’s quite another to loudly proclaim your own marriage wonderful while dismissing everyone else’s as clearly miserable.

I wrote Foreverland because I was craving a more compassionate portrait of the enormous challenges of married life. Trying to tolerate the same flawed person until you’re dead is funny! Yet so many discussions about marriage today are incredibly solemn and moralistic, so absolute and unforgiving, always boiling down to the fearful proposition that a married person could never – should never – land in a gray area: You’re either walking on air together or you should get divorced immediately!

Personally, I want to read and talk about the uneven realities of trying to love someone through many different stages of your life. It’s an unpredictable ride, even when you’re happy together and you acknowledge that often. I want books and online discussions about marriage to have more in common with the honest conversations I have with married friends who admit the frustrations and even the anger that arises from trying to accept and embrace another mortal human from the day you marry until the day you die. In my book, I wanted to capture the joys and also the disappointments of falling in love, getting married, and managing three kids, two jobs, and several high-strung dogs, from the newlywed years through our ongoing pandemic, without turning against each other for no good reason, other than we were just exhausted.

But I also wanted to wrestle with the emotional and imaginative freedom that comes from feeling extremely safe in your marriage. When I started my book, I knew at some gut level that I’d probably never leave my husband, and he seemed in it for life, too. So we started to have long conversations about the ways we could theoretically grow apart some day. Instead of feeling scary, these discussions felt invigorating: by allowing room for doubts – and imagination, and longing – we not only rediscovered our commitment to each other, but we opened up a wider conversation about how we wanted to live as we got older. Honest talks that initially felt a little risky ended up deepening our understanding of why we’re together.

As the pandemic set in and my book and my marriage both started to feel more and more like an interesting and weird thought experiment, I took more intellectual and emotional risks, if only inside my mind: What was it like to cheat? How great would it be to lie to the one person you’re always completely honest with? These were thoughts that started on the page, and then evolved into open discussions with my husband who, much to his credit, was invigorated by the honesty and the ideas in the mix, rather than threatened by them.

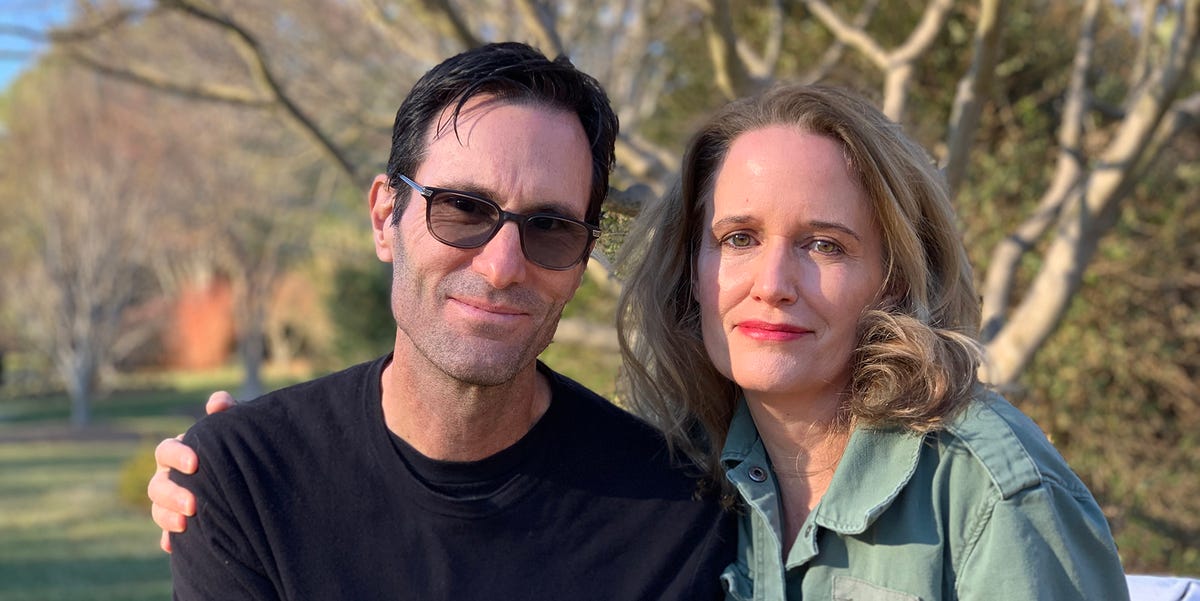

But let me make it clear that my husband Bill and I are not always so good at this job of being married. During the pandemic, when we were trapped in the same house for months on end, we knew life would be tough. We both get overwhelmed and defensive when we’re stressed out. So we made time to slow down and talk about absolutely everything – our daydreams, our obsessions, our stupidest preoccupations, our most ridiculous notions. Along the way, we made a new commitment to honoring each other’s deepest desires, and to cultivating compassion for whatever we heard pouring out of each other’s mouths, from trivial musings to fundamental beliefs.

One afternoon when Bill had a cold, I wrote half a chapter about the bad noises he makes when he’s phlegmy. I kept stopping and laughing while I was writing, and finally he asked to read what was so funny. Then he was laughing, and coughing, and sneezing and laughing some more.

That chapter was published by the New York Times over the holidays, and it made a lot of people angry. If you hate your husband so much, why don’t you just file for divorce? people wrote in the comments. This suggestion felt as odd to me as someone walking into a party full of my married friends and insisting that the whole laughing gaggle of us call our lawyers immediately.

Why was anger in a marriage so repugnant to so many people? How had the old familiar notion that passion arises out of some strange dance of love and hate been encountered as so threatening? Even the obvious joke “Do I hate my husband? Oh sure, yes, definitely,” had been taken literally, despite my referring to him as “my favorite person.”

Like so many other discussions at this volatile time, our wider conversation about marriage keeps migrating toward binary extremes of adoration and contempt, happiness and divorce, forever and only right now, when what I’d set out to write was exactly the opposite: an acknowledgement that human lives aren’t easily reduced to such simple, unconflicted descriptions. We are all complex, ferocious, sublime animals, capable of love and hate and everything in between, capable of joy and frustration, bickering and whole-body communion, annoyance and admiration and big, imaginative leaps of faith. But the extreme stress of the pandemic, combined with hostile partisan politics and the tendency of social media to reduce every complicated issue into two oversimplified extremes, has rendered many of us more self-protective and less open than usual – to our own feelings and everyone else’s.

Relocating our senses of humor about marriage – our failures, our shortcomings, the way we struggle just to love and be loved – is good for us. Because the goal is not either to stay married forever or to conclude quickly that a marriage is done for. Love flourishes and blooms in the gray area in between these rigid poles. And when we’re as honest as we can possibly be, our marriages and our lives in general feel more free, not less. That’s the possibility that lives in between “blissful” and “doomed”: the exuberant passions and mundane satisfactions of an ordinary life.

Heather Havrilesky’s new book, Foreverland: On the Divine Tedium of Marriage, is now available from your favorite bookseller. This essay is part of a series highlighting the Good Housekeeping Book Club — you can join the conversation and check out more of our favorite book recommendations.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io