Child beauty pageants have long been a part of American culture, particularly in the South. Those who support these types of contests say they’re not just about beauty, being judged or winning prizes — though there have always been plenty of prizes to go around — but about being a responsible, talented and well-behaved girl. A backlash naturally occurred in the wake of the 1996 murder of 6-year-old pageant contestant JonBenet Ramsey. That’s when Lise Hilboldt-Stolley investigated this complex, often contradictory world in a time before social media and shows like Toddlers & Tiaras. This deep dive into the pressured-filled, misunderstood world of child pageants, from the February 1999 issue of Good Housekeeping, is brilliantly reported and deeply humane. — Alex Belth, Hearst archivist

There’s something different about Thumper Gosney. Playing in the pool at the Atlanta Airport Marriott, the 8-year-old moves with a dancer’s grace, her waist-length hair spreading like seaweed around her. She’s a magnet for younger kids: Two little girls wearing water wings float around her, and the three form a spontaneous family.

Thumper (real name: Leslie) displays confidence and independence, qualities her mother is eager to cultivate. Susan Gosney and her husband, Gary, are older parents — Thumper’s three sisters are already in their 20s — and they want their youngest to flourish on her own.

More From Good Housekeeping

In fact, Thumper used to be quite shy, according to her mother. But that was before the pageants. At age 5, Thumper visited a county fair near the Gosneys’ hometown of Temple, TX, where a beauty competition is held each year. Captivated by pictures of the sparkling crowns and ornate dresses worn by the previous year’s winners, Thumper begged her mother to let her enter. Susan agreed. “I bought her a beautiful dress,” Susan recalls. “But I did everything wrong. I put her hair up in a bun, real tight, to show off the dress. I wetted it, real slick. She looked like a peeled grape in that big dress.”

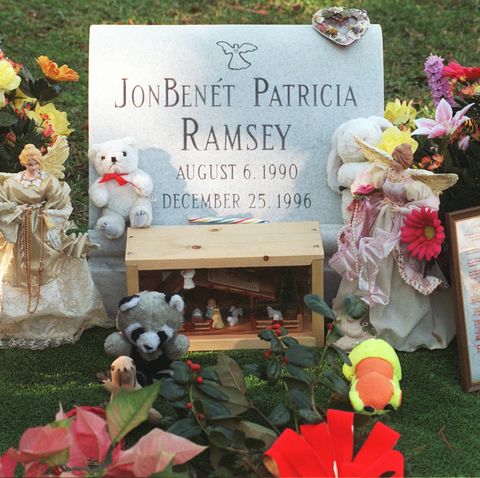

When JonBenet died, the Gosneys were stunned. Thumper sent flowers to her little friend’s funeral. And then everything began to change.

Thumper went on to lose her first five pageants. “I didn’t care,” she says now. “They were fun. I got to make new friends.” Within a couple of years, she had won a large number of state titles and had moved on to national competitions.

Thumper, Susan and Susan’s mother, Jerry, are in Atlanta for the Universal/Southern Charm National Pageant. (Gary, a veterinarian, would be here, too, if it didn’t mean shutting down his animal clinic for the weekend and missing the Sunday school class he’s taught for 27 years.) Charm, as the pageant is known, has been around for 16 years and is one of the most competitive. Contestants range in age from under a year to twenty-something and come from all over the country. “Everyone knows it’s hard to win,” says Susan. “You’re competing with the cream of the crop.”

The Gosneys have arrived a day early to give Thumper a chance to relax, while Susan gets her daughter’s closets ready. Charm requires elaborate outfits for each of its categories, and families often transport trunks of gear in vans and Winnebagos. But the Gosneys live too far away to drive, so Susan carried Thumper’s two fanciest pageant dresses on the plane in a huge Rubbermaid plastic box, along with her irreplaceable submissions for the picture competitions, Photogenic and Portfolio. She packed a rolling footlocker for the rest of Thumper’s costumes and a black case for makeup and three sets of hot rollers.

“That’s all Thumper’s,” Susan says with pride, pointing to her daughter’s tresses. “Most of these girls will be wearing hair extensions. We are using false eyelashes, though. You get the same effect with mascara, but false eyelashes are easier on the eyes than 14 coats of mascara. You just drop them on.”

Thumper has emerged from the pool and is launching into the routine she’ll do for the modeling competition. She flings a towel — substituting for a cape — over her wet shoulder, spins several times and with a whoosh drops the towel to her forearm. She catches it perfectly.

It was in this hotel, in Atlanta, that Thumper Gosney met JonBenet Ramsey, five months before the pretty blond 6-year-old was found murdered in the basement of her Boulder, CO, home on December 26, 1996. The girls were competing in the same age group at the Sunburst International Pageant, though JonBenet was something of a novice, having competed only in local Colorado contests.

Susan first noticed JonBenet in the pageant book. “When you get to a pageant, you look to see who your competition is,” Susan say. “I remember saying, ‘That’s one beautiful child.’ So many kids look like cookie-cutter cutouts. Their families hire the same hair and makeup people. But she was naturally gorgeous. And she was brand-new.”

JonBenet was transfixed by Thumper’s talent routine, Susan remembers, a rendition of a Patsy Cline number entitled “She’s Got You.” Playing a scorned girlfriend, Thumper yanked various objects — including love letters, records, even a pair of junior golf clubs — out of her evening gown. “JonBenet wanted to know how she got all that stuff in her dress,” says Susan.

“You looked up to Miss America. She had poise, she was beautiful. She was the ideal woman.”

Thumper and JonBenet became friends and played together. The Gosneys found JonBenet to be sweet, quiet and unaffected. Patsy Ramsey, her mother, though mostly friendly, at one point became standoff-ish. The Gosneys were intrigued by JonBenet’s black-and-white costumes (most pageant dresses are in vibrant colors) and asked Patsy about her dressmaker. “She gave short answers,” Susan recalls, “as if we were trying to steal her ideas.”

When JonBenet died, the Gosneys were stunned. Thumper sent flowers to her little friend’s funeral. And then everything began to change.

Pageants celebrating female beauty and charm have been fixtures at fairs and festivals in the United States since the 19th century. But their rise in popularity probably dates to 1954, when the Miss America pageant was first broadcast on television. Susan Gosney remembers the first time her family saw the show. “You looked up to Miss America,” she recalls. “She had poise, she was beautiful. She was the ideal woman.”

Little girls began dreaming of one day becoming Miss America. And some pageants wanted to give them a head start. In 1960, a Miami broadcaster hosted the first locally televised pageant for children, Little Miss Universe. By the 1980s, child pageants had become an inextricable part of life in the South, proliferating by word of mouth, without any national advertising or publicity. Children became “names” on the circuit but remained unknown outside the pageant world.

“Pageants didn’t kill JonBenet. A terrible person did.”

If not for JonBenet’s murder, that world might have thrived in relative anonymity. But in the media frenzy following her death, pageants were condemned, even demonized. Americans were shocked by images of little girls in bejeweled dresses imitating grown-up beauty queens. And in a time of heightened concern about child abuse, pageant children were seen as having been robbed of their innocence by being taught to behave in sexually provocative ways. As a result, newcomers were scared away from the contests and enrollment plunged. At the same time, pageant families suddenly found themselves hounded by reporters and insulted by strangers.

At a pageant in Dallas recently, Susan Gosney reports, a group of salesmen caught sight of Thumper on her way to the ballroom. One of the men loudly remarked, “I think it’s appalling you force that poor child to wear makeup like that.” His words stung.

“I’m not a pushy stage mother,” Susan insists. “My daughter loves our weekends together, loves dressing up, loves doing her talent routine … Pageants didn’t kill JonBenet,” she adds emphatically. “A terrible person did.”

Faye DeMatteo, the mother of Rayanna, one of last year’s winners at Charm, says that her family had to change their phone number twice to avoid reporters. She refused to talk to any of them and was outraged by comments made by Geraldo Rivera on his TV show: “He said that when he sees a 6-year-old in a swimsuit, he sees sex. Well, that’s his perception. When I see a 6-year-old in a swimsuit, I see a 6-year-old in a swimsuit.”

“People misunderstand pageant kids. They have good manners, high self-esteem and they know how to act in public.”

Pageant moms believe the media look through a distorted lens. And they charge that the heaviest criticism comes from people who have never even been to child beauty pageants. After psychologists and a former Miss American appeared on television to talk about the emotional damage inflicted on pageant kids, Faye and other mothers sprang into action. “We called psychological institutes across the country,” she says, “even the Mayo Clinic. There are no studies.* They can’t produce anything to prove adverse effects.”

Over and over, pageant mothers insist that their children want to participate and are not subjected to the perfectionist pressures imposed on child actors or athletes. Indeed, their behavior in competition can be charmingly unpredictable. “When Rayanna was 3,” Faye recalls, “she walked downstage toward the judges, bent down, and yanked off her shoes. ‘These shoes hurt,’ she announced. Then she set the shoes down, finished modeling, blew a kiss — and still won the top title.”

Some of the regulars say that pageants help young girls the way charm schools once did. “People misunderstand pageant kids,” argues Francis Clinton, grandmother of two contestants at Charm. “They have good manners, high self-esteem and they know how to act in public. You can go into a restaurant and see a table of pageant kids eating quietly, surrounded by rowdy, badly behaved kids all over the place.”

Pageants may be “politically incorrect,” as Faye notes, but they are also free of such scourges as drugs, alcohol and gangs. And besides, she adds, “There are a lot worse things you could subject your child to than spending time with her.”

After JonBenet was killed, some pageant families began worrying about the safety of their children. “If people talked to you in the elevator, you’d get paranoid,” says Diana Pote, mother of Charm contestant Alexandra. That fear has receded, but not the remarks. “I had one lady say [about my daughter], ‘Oh, that poor baby.’ It made me furious.” Incidents like these have made pageant families more cautious, though. Now mothers scrub their daughter’s faces and take down their hair as soon as a contest is over. And the girls themselves have stopped telling schoolmates what they do on weekends. Pageants have become a secret shared only with pageant friends.

Charm registration begins Friday around noon, as a line forms outside the Marriott ballroom. Faye DeMatteo, wearing a red-and-white polka dot outfit that matches her daughter’s, greets everyone and hands out Charm T-shirts.

Seated behind the registration desk is Darlene Burgess, who founded Charm with her husband, Jerry, in 1982, partly because their daughter, Becky, loved to compete. Becky is now 27 and has a 4-year-old daughter who’s also on the circuit. Darlene spends time with each applicant, answering questions and giving advice about which photographs to submit. “Not this one,” Darlene tells a mother. “We don’t do swimsuits anymore, and she’s got shadows under her eyes.” A pleasant-faced woman with a lilting Arkansan accent, Darlene has the air of a country doctor. “This one’s a cutter,” she says.

“I’ve seen people act uglier at Little League baseball games [than] at pageants.”

In 1997, Darlene and Jerry say they lost more than $25,000 on Charm, as paid entries dropped from 200 to 68. “We didn’t get any babies at all,” says Darlene. Another casualty is Charm’s pageant book, which once attracted more than 100 pages of ads from local businesses. In 1997 and 1998, only a handful of ads were sold. The number of entrants remains low, but the Burgesses have reduced the amount of their cash awards and figure they’ll break about even.

Loyal pageant families are undeterred by the bad publicity and continue to support what they see as a wholesale family activity. Says Hugh Roberts, the doting grandfather of Charm contestant Ashlee Golden, “I’ve seen people act uglier at Little League baseball games [than] at pageants.”

But Little League has got to be cheaper: Entry fees for Charm now start at $395, with additional charges for special categories like Portfolio and Talent. It’s possible, with multiple submissions, to spend more than $1,000 just to enter. Then there are the pageant dresses, which range from $300 to several thousand dollars each. Hairstyling and makeup costs for the two-and-a-half-day pageant range from $175 to $350. And to prepare for the event, many children take modeling lessons with a coach, costing up to $85 per hour. There’s also the expense of makeup and hairstyling for studio photographs.

To help cover costs, many pageant parents work as hairdressers, makeup artists, costume designers or modeling coaches. Susan Gosney runs a store in Temple where she sells cribs, children’s clothes and pageant dresses; a former dance teacher, she also coaches children and designs clothes.

Since Thumper began competing, she’s won more than $20,000 in U.S. savings bonds. But Susan doesn’t want to think about what the family has spent — and she’s grateful her husband doesn’t ask.

It’s Friday afternoon, and the talent competition is about to begin in the brightly lit, heavily chilled ballroom. No tickets are sold at the door, and no strangers are in the house — just pageant families. Thumper glides into the ballroom wearing a yellow chiffon dress that Susan has decorated with silk flowers and a cluster of pearls. Her hair, swept off her forehead, cascades into a huge flip at her lower back, like a bond waterfall. “It takes 45 minutes just to roll her hair,” Susan says.

Three judges — all women with pageant backgrounds — are seated at a long table, a few feet from the stage, their backs to the audience. “It’s not just a voice, but also about showmanship and performance,” explains judge Marie Mobley, a former contestant who now works as a flight attendant. “You can have a great voice, but sing the wrong song.” And when the competition is close, she adds, “winning can come down to an uneven hem, or the wrong accessory. It can be the parent’s fault.”

Talent contestants are allowed approximately three minutes onstage; exceeding the time limit may cost points. As the girls take their turns, cries of “Go girl!” ring out. Cheering is especially loud for contestants who have surmounted personal obstacles: a teenager from Florida who tap-dances on a foot recently removed from a cast; a 12-year-old who, after seven years of speech therapy, manages to fly through a tongue-twisting country and western ditty; a 12-year-old Indian girl singing a powerful rendition of “Amazing Grace.” (The audience knows that the girl was abandoned as an infant on the streets of Calcutta and adopted by a loving family from the Midwest.)

One of the girls in Thumper’s age group belts out a Broadway tune; another dances the can-can. There are the usual mishaps: One girl drops a baton; another trips on her feather boa. Finally, it’s Thumper’s turn. Susan gives her daughter a careful kiss, so as not to mess up her makeup, then runs to the center of the house to root for her.

Wearing a big smile, Thumper sings “Baby Face” into a handheld mike. She is funny and charming, though her voice seems a little thin. During the song, Thumper rocks her hips and points her finger at her cheeks and chin. She is at once coy and innocent, like a latter-day Shirley Temple. If there is something mildly disconcerting about a child performing this number, no one seems to notice.

At Charm, the talent competition does not count toward Supreme Queen — the most important title in the pageant — and Susan is already cutting her losses. “We’re doing this for practice,” she offers. “It’s not her normal talent routine. Thumper is a real beginner singer.”

For the beauty competition Saturday morning, Thumper is made up by Toni, a pretty, young mother who was herself a beauty queen and whose infant daughter now competes. She charges Susan $250 for two days. “Toni makes Thumper prettier than anyone else,” says Susan.

Dresses for the Beauty segment are elaborate: Thumper’s is made with pale-peach crepe and decorated with velvet roses, clusters of pearls and rhinestone applique. It shimmers under the lights.

Although she knows some people are critical of the practice, Susan has Thumper’s hair colored. “The last 12 inches were blond from swimming [in chlorinated pools],” she explains. “When we put it up, her roots were so dark, it looked like she was wearing a false hairpiece. I had her hair highlighted to even it out. Now she looks more natural than when she was natural.”

Susan knows that the kids who appear joyful and spontaneous onstage have a better chance of winning — which is why she’s so concerned about Thumper’s smile. “Thumper recently picked up a habit of locking a freeze smile on her face,” Susan says. “It’s not genuine. I told her to flat-out smile. That’s what the judges want to see.”

As they head to the ballroom, Susan asks Thumper, “What do you do when you turn around onstage?”

“Monkey lips,” Thunder replies, laughing a the words.

Susan explains: “When she turns upstage, she throws her lips out like a monkey. It relaxes them. Then when she turns back to the judges, she has a natural smile.”

Charm’s Beauty competition begins with the youngest group — children 1-year-old and under, helped onstage by their parents. Things move quickly, and it isn’t long before the emcee calls the older girls.

“Do you want to say a prayer before you go on?” a pretty woman asks her 7-year-old granddaughter. Together they bow their heads. “The light of God surrounds me. The love of God enfolds me.” Just before her entrance, the girl is reminded to “flow like the angels.”

Now master of ceremonies Tim Whitmer, a handsome former Air Force sergeant, is crying out, “Welcome number 74, Thumper Gosney!” To the accompaniment of mellow synthesizer music, Thumper floats across the stage. Just about the judge’s table, she performs a universal turn, crossing one foot over the other and slowly rotating — all the while keeping her eyes locked on the judges. Her broad smile is dazzling: The monkey lips have worked.

“Thumper’s ambition is to be a veterinarian and a cartoonist,” Tim announces. Her score is 29.7 out of a possible 30.

After Beauty, Thumper changes into a coral pantsuit for the modeling competition. Pageant modeling is like a choreographed dance, a series of spins, struts, sassy poses, smiles and pouts, all performed at breakneck speed. Thumper’s choreography was changed just a few days ago, and Susan is concerned that her daughter’s under-rehearsed moves may be forgotten.

Thumper learns quickly, according to her mother, but she doesn’t particularly like to rehearse. At home, “she’d rather draw or watch the Disney Channel or play on her computer or work on math. She’s a couch potato.” Thumper isn’t always so well groomed, either. “For school, you can’t get a bow on her,” Susan complains, “or even get her to brush her teeth or comb her hair.” Apparently, it takes an audience to bring out the competitor in Thumper. “She absolutely loves being onstage,” Susan says. “She can’t wait to get out there.”

“All the girls in JonBenet’s group from Dream Star bought an eternal light for her grave.”

Now Thumper hears her dance music and shoots across the stage. Though she seems a little tentative at first, her movements are clean and precise. At one point, she swings her cape over her head, back and forth, like a matador. Then, just as she did poolside, Thumper drops the cape and catches it on her forearm.

Her scores are almost perfect. Thumper now has a chance of winning Supreme.

Next comes her favorite part: Western Wear. “That’s because I don’t have to wear pantyhose,” Thumper says with a grin, “I can wear socks in my boots.” Drenched in spangles, sequins and glitter, Western Wear costumes are amazingly intricate. In a flash, Thumper is decked out in a neon lime-green coat trimmed with dyed-to-match fox fur. The mid-thigh-length coat conceals a sleeveless top and pair of shorts — covered, hula-style with shimmering gold disks — that she reveals midway through the number. Thumper attacks her routine with relish, pumping her knees and elbows and leaping in the air to click her heels. She pulls another top score.

Pageant outfits are frequently resold and refitted. Although Thumper’s Western Wear costume originally cost $2,200, Susan picked it up from another pageant mother for much less.

“People sell their clothes because their children have outgrown them, or they want a new look,” says Faye DeMatteo. Some mothers think that buying a dress from a winner will help their own child’s chances.

JonBenet’s mother, Patsy Ramsey, was in the market for some custom-made costumes at a local pageant called Dream Star held in Rome, GA, over Thanksgiving weekend, 1996. After striking up a conversation with Faye in a restaurant, Patsy asked about the outfits she was selling. Patsy ended up buying Rayanna’s fancy white pageant dress, made of silk organza. One month later, JonBenet was buried in it.

The DeMatteos went to the funeral. “All the girls in JonBenet’s group from Dream Star bought an eternal light for her grave,” says Faye.

Sunday morning, there is a prayer service in the ballroom conducted by pageant sound technician Larry Cole. “We are all God’s children,” Larry tells his sleepy-eyed audience. “Just as we watch over and guide our children, God watches us.”

After devotionals, Larry plays the soundtrack from Gone With the Wind, as the emcee announces contestants for the final competition — Southern Belle, featuring designs and fabrics true to the Civil War period. Girls waft in wearing large hoopskirts of velvet and silk, their capes trimmed with lace or fur, and their hair heaped in tight ringlets. Many look like miniature Scarlett O’Haras.

Thumper seems intimidated by the costumes of her competitors. “I think the other dresses are prettier than mine,” she says. “They’re so fancy.” Actually, Susan has gotten compliments for the simplicity of Thumper’s outfit — a pale aqua dress with short puffed sleeves and lacy pantaloons. Susan came up with the design after extensive library research, and she is proud of the result.

When it’s her turn, Thumper moves downstage fanning herself and twirling her parasol. Demurely, she lifts her skirt in front of the judges to reveal the pantaloons. Then, as she begins a universal turn, her fan suddenly falls to the ground. This could cost her serious points, but Thumper doesn’t flinch. She continues her turn, curtsying when her back is to the judges and retrieving her fan as if the whole thing had been deliberate.

“She did it so smoothly,” Susan says, “the judges didn’t even notice.”

But they do notice the peach ribbon sewed into Thumper’s pantaloons. Civil War children apparently did not have colored ribbons in their undergarments, and the mistake costs Thumper two-tenths of a point. Susan is mortified.

On Sunday evening, everyone dresses for the crowning. The girls have changed back into their Beauty gowns and touched up their hair and makeup onstage. Orange, pink and yellow lights flash behind the silver curtain, as the soundtrack from The Bridges of Madison County plays over the loudspeakers.

There are so many awards, so many alternates, it’s almost impossible to keep track. Dozens of plaques and trophies are presented to each age group, passed out by last year’s winners, known as Charm Royalty. The emcee rushes through the names, as the audience shouts and claps. All the contestants seem to walk away carrying something.

“Pageants will make a comeback. Because everybody thinks their babies are pretty.”

When Thumper’s group takes the stage, the emcee calls out her name again and again, as she sweeps her division, winning Dream Girl and the coveted National Beauty Queen. Strung with banners, Thumper is fitted with a rhinestone tiara as the audience applauds wildly. Susan is shouting and hugging her daughter. Standing beside a five-foot-high glittering trophy, Thumper grins from ear to ear.

But it is a 5-year-old Leslie Butler who wins Supreme Queen, scoring six-tenths of a point ahead of Thumper. Leslie has two dads who are famous pageant coaches — her real father, Michael Butler, and his partner in business and in life, Shane King. Michael was awarded custody of Leslie when she was an infant, and he started her in pageants at the age of 3 months. (He carried her onstage in a pink dress, and she slept through the whole thing—and won.) Now the two men rush to the stage and sweep Leslie off her feet.

Thumper insists she isn’t bothered by losing Supreme Queen. And she notes with satisfaction that “National Beauty Queen gets the same-size crown as Supreme. It’s just not the same title.” Susan, too, is pleased, pointing out that Thumper has won a total of $2,400 in savings bonds. But Susan is still upset about the peach ribbon. Later she will learn that the judges for the Photogenic and Portfolio competitions thought Thumper was wearing too much makeup in her pictures. And that it was the makeup problem that probably cost her the crown.

For her part, Darlene Burgess has begun to feel more confident about Charm’s future. “Pageants will make a comeback,” she predicts, “Because everybody thinks their babies are pretty.”

The lights come up in the ballroom, and the contestants revert to ordinary little girls, charging around and pestering their parents. They want to play with their new friends. They want to shed their dresses, take down their hair, order room-service pizza, watch a video and organize a slumber party.

Thumper wants to swim. “Come on, Mom,” she says, bouncing up and down and tugging Susan’s arm. “Let’s go right now!” Still flushed with pride, Susan gathers up her daughter’s trophies and follows along.

*Editors Note: Since the time of publication in 1999, studies have been conducted around the emotional impact of childhood beauty pageants. Some have linked participation in childhood beauty pageants to possible adult body dissatisfaction, interpersonal distrust and impulse dysregulation.