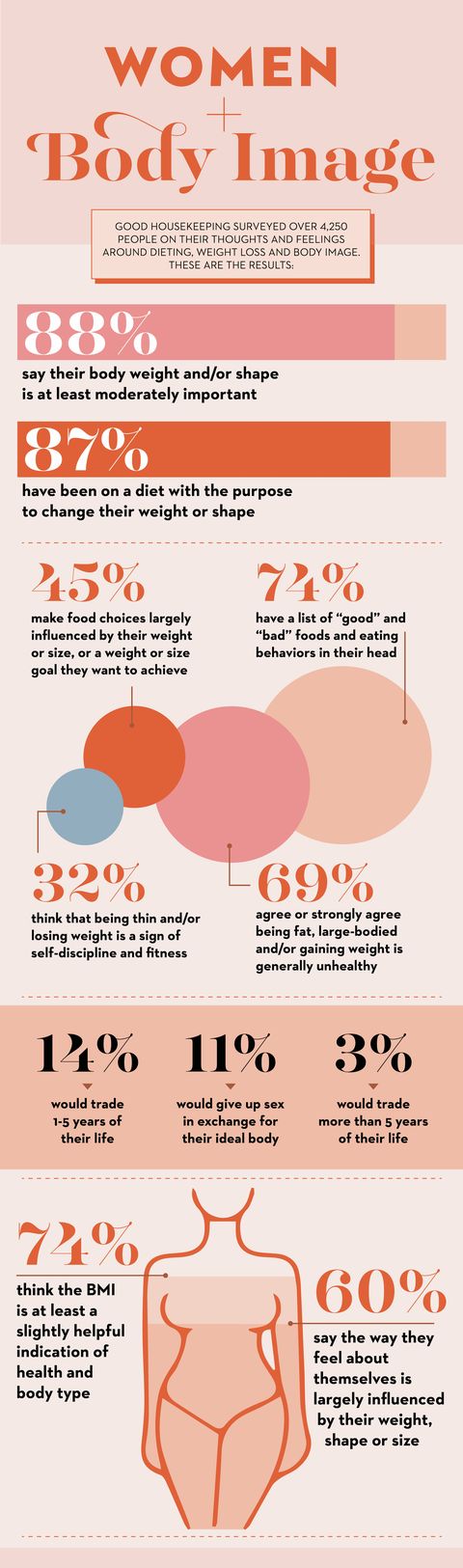

Over the last year, Good Housekeeping has been exploring the impact of diet culture with our anti-diet series — a combination of personal stories, expert advice, historical context and cultural insights. Throughout this series, we also explore the many facets of the anti-diet movement, including fighting fatphobia, understanding thin privilege and how the BMI came to be used as a measure of health.

To round out this reporting, we surveyed our readers, as well as the audiences from our sister publications Cosmopolitan, Woman’s Day and Prevention. We asked a variety of questions around body image, weight loss and dieting, some pulled directly from the National Eating Disorders Association’s Eating Disorder Screening Tool, which aims to help people decide whether they want to seek professional help for their thoughts and behaviors around food and body image.

Diet culture’s force and influence can make some people — especially women — feel like they must constantly strive to be different than they are in order to be happy, successful, beautiful and worthy. Sure enough, our survey results indicate that 87% of respondents have been on a diet with the purpose, at least in part, to change their weight or shape. Meanwhile, only 6% of respondents strongly agreed that they feel generally happy with their bodies, and a sobering 17% said they’d be willing to shave a year or more off their lives in exchange for their ideal body.

Below, you’ll see what else we learned from more than 4,250 respondents — and benefit from the advice gleaned from the dozens of nutritionists, dietitians, fitness experts and mental health professionals our editors spoke with this past year. The hope is that instead of gauging our self-worth by our weight, shape and size, we would start to feel satisfied with how we look, and, more importantly, find joy in who we are, how we feel and the way we live.

The majority of people are unhappy with their bodies.

Because our readers are mostly a wide swath of American women, we weren’t shocked to discover that many of them are not thrilled with the way they look, and that this opinion of their physicality has leaked over into the way they feel about themselves in general.

- 48% of respondents disagree or strongly disagree that they are happy with the way their bodies look and feel. Only 6% of respondents strongly agree that they feel generally happy with their bodies.

- 60% of respondents say the way they feel about themselves is largely influenced by their weight, shape or size. Feeling insecure or otherwise blah is part of being human, but regularly deriving most of our self-worth from the way our bodies look, experts say, can leave us tangled in a loop of doubt, shame, isolation and negative self-talk that can keep us from being social, feeling happy and living well. To stop the cycle, pros suggest adopting an attitude of body neutrality (a.k.a. accepting our bodies as they are) to help free up our minds to think about things that are far more important and impactful than the way we happen to look on any given day.

The extremes people are willing to go to to look a certain way, are, well, extreme.

- 17% said they’d shave years off their lives in exchange for their ideal body. 14% would trade one to five years of their life; 3% would trade more than five years of their life. 11% of respondents said they would give up sex in exchange for their ideal body, 25% would trade an entire category of food and another 13% would give up the chance to travel and see the world.

The fact that so many of our respondents would be willing to dull the vibrancy of a fully lived life to look a certain way clearly speaks to how badly some of us want to be thinner. But it may not feel so great to have such an elusive goal mean so much compared to other priorities in our lives. Changing the way we think about our bodies isn’t an overnight thing, say the experts we spoke to, but it’s worth the effort. Below are some resources, tips and how-tos to break the cycle:

Many of us engage in disordered eating behaviors.

Here’s the reality: So much of how we are taught to eat from childhood onwards is disordered, as reported in our article on the topic. In fact, psychologists we spoke to assert that disordered eating is so normalized that most of us won’t even register it as problematic. For example, these common behaviors can be an indication of disordered eating when they preoccupy a person or cause them stress, according to professionals we interviewed: Eating only during specific time windows, deeming entire categories of food (like dessert or anything fried) as “bad” and making food decisions based on numbers (whether calories on a label, the number on the scale or jeans size) rather than based on internal signals. One survey even found that 75% of American women engage in disordered eating behaviors like the below, which makes it the norm in the U.S., so our results aren’t astonishing — but they’re still sobering.

- 42% say when they eat certain things or a certain amount of food, they feel the need to “make up” for it. Enjoying a meal with friends and then everyone swearing not to eat for a week or heading straight to the gym is a common bonding ritual, as one of our expert contributors wrote. But as “normal” as this behavior is, it can be unhealthy. For many people, focusing on calories consumed or burned can fuel obsessive thinking and deprivation, which can lead to binge eating and/or restrictive behaviors, as reported by Good Housekeeping’s Registered Dietitian.

- 45% of respondents make food choices largely influenced by their weight or size, or a weight or size goal they want to achieve. Nearly half of our survey respondents said they make food choices based on the way their bodies look. But anti-diet nutritionists and advocates advise instead tuning in to the type and amount of food your body is asking for by asking questions like, how hungry am I? What will make me feel good right now? This is called intuitive eating, an approach to eating based on 10 core principles to let your own body guide you in what, when and how much to eat. Many proponents have found that intuitive eating helps them break free of the preoccupation with the appearance of their bodies and self-judgment around food.

- 74% of respondents have a list of “good” and “bad” foods and eating behaviors in their head. Assigning moral virtue to food can be problematic for myriad reasons, says GH’s Registered Dietitian, but largely, it suggests we’re doing something “wrong” when we opt for the things our bodies naturally crave, leading to unhelpful shame. Anti-diet culture dietitians and psychologists suggest reminding ourselves: Whether we eat a cookie or eat a salad, our food choices have no bearing on whether or not we are good people, worthy of respect, love and compassion.

Anyone feeling like they are suffering from disordered eating or an eating disorder can and should reach out for help immediately. The NEDA helpline at (800) 931-2237 is available daily via call or text.

Nearly three-quarters of respondents place importance on body mass index (BMI).

- 74% think the BMI is at least a slightly helpful indication of health and body type. This belief, of course, makes sense — the BMI has long been used as a benchmark for health everywhere from grade schools to doctors’ offices. But what many people don’t realize is that this formula was not designed to be an indicator of health, and in fact yields flawed — and potentially stigmatizing — findings, especially for Black people and other people of color. Fortunately, an increasing number of healthcare professionals are coming to believe that the BMI is an outdated and incorrect measurement of health, as we’ve learned in our reporting.

In short, A “normal” BMI actually doesn’t automatically denote good health, and an “obese” BMI doesn’t automatically denote poor health. What may matter more for our health than the BMI are blood pressure, cholesterol, blood sugar, hormone levels and any regularly-practiced health-supporting behaviors, such as exercising, according to the doctors we spoke with.

Many people confuse thinness with wellness — and fatness with poor health.

- 51% of respondents agree or strongly agree that being thin/and or losing weight is generally a way to get healthier. In truth, we’ve learned in our research that it’s nowhere near that simple. Despite all the smiling faces from the “after” pictures in diet and fitness ads, experts say that being thin is not, in fact, necessarily the same thing as being healthy. Other medical professionals we spoke to pointed out that the idea of weight causing negative health outcomes isn’t well supported by the data, and anyone can be smaller-bodied and unhealthy.

- 69% of respondents agree or strongly agree being fat, large-bodied and/or gaining weight is generally unhealthy. Just as we tend to collectively believe that thinness is inherently healthy, the opposite is also true: We believe higher weights are inherently less healthy, as reflected in our survey findings. The reality, though, according to experts, is that it’s just as possible to be perfectly healthy even if you’re larger-bodied or “overweight,” and it’s impossible to know anything about a given person’s health by only looking at their body size.

- 32% think that being thin and/or losing weight is a sign of self-discipline and fitness. The same messaging that makes us believe that thinness is a synonym for health has also made many of us believe that anyone in a smaller body is doing something “right” — but pros say weight and shape are generally inherited, not chosen. Still, this long-held belief has led to something called “thin privilege,” which refers to the benefits granted to smaller-bodied people, including the assumption that they are living life virtuously and correctly, and those who are in a bigger body are failing on both counts.

- 22% think being fat or large-bodied is a sign of laziness and/or lack of self-control; 16% think being fat or large-bodied is a choice. Inverse to thin privilege is fatphobia, the fear and hatred of fat bodies that perpetuates negative stereotypes about and discrimination toward larger-bodied folks, who in turn can suffer socially, medically, mentally and financially as result, as we’ve reported. The belief that larger-bodied people are doing something “wrong” is a byproduct of fatphobia, but just as we can’t choose our height or hair color, experts say that most people are simply unable to tailor their body weight or size.

We can shape a future where we feel satisfied with our bodies.

- 62% of respondents who are parents talk about food or exercise with their children as they pertain to weight. While every parent aims to do their very best for and by their children, most mainstream healthy eating advice tends to be heavily influenced by diet culture. This can mean that we unwittingly engrain harmful patterns, as one author, a nutritionist, writes in her piece on how to raise a child with positive body image. Avoiding pressuring a child to eat or abstain from certain foods, noticing changes in a child’s eating, practicing anti-diet culture speech and embracing body diversity, she says, can set kids up to be more resistant to disordered eating and shame around food and their bodies.

- While 35% of respondents believe our society is generally becoming more body positive and size-inclusive, 65% believe our society has a lot more work to do. We agree, and at GH, we aim to continue the conversation about weight, diets and body modification in a way that meets people where they are. Our goal, in part, is to carry on sharing reliable, science-backed information and respect the choices our readers make while moving the needle toward a more holistic view of health and wellness.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io