It was March 25, 2020, just as New York had gone into lockdown as the emerging epicenter of the pandemic, when a healthcare professional I’d never met in real life presented me with an impossible choice. Either I’d risk dying in my sleep of what she called a possible pulmonary embolism or head to an emergency room where COVID-19 was rampantly spreading like wildfire. “It could be a panic attack,” the doctor said, adding, “I’d suggest you’d go to the ER to rule out a blood clot.”

Maskless along with hundreds of others, I’d just returned home a few days prior on a flight from London, where I was visiting my boyfriend. Then, COVID-19 came for New York, replacing its usual bustle with an eerie stillness. It was a taste of things to come when we were greeted on the jet bridge with a fleet of nurses to take everyone’s temperature.

This long, international flight was the reason the doctor thought a blood clot might have caused the incident and urged me to seek emergency treatment.

As far as a panic attack goes, I’d actually never experienced one before — but I wasn’t surprised that this feeling could be a legit attack. I’m prone to feeling anxious, but at the time (terrifying news cycle notwithstanding!) I had felt relatively good. Even though I’d just lost my full-time job in a New York restaurant, I’d already found a silver lining: I’d pursue more writing with my newfound time. I’d go so far as to say I was in high spirits that afternoon, all things considered, feeling motivated after having just submitted an article to an editor.

It all happened so fast in an otherwise quiet environment, as I had just sat down at my desk to start a new assignment. My body started sending extreme distress signals, one right after the other — if I could venture a guess, it physically felt like my body was warning me that I was about to die.

My sinus cavities started pulsing. I could actually feel them expanding and contracting, like there was a balloon behind my eyes that was continually inflating and deflating. My pulse skyrocketed, along with my temperature, my shirt suddenly drenched in sweat. My heartbeat was loud enough to thunder in my ears.

I staggered away from my desk and was about to cry out to my roommate for help when a swell of energy started making its way upward, rendering me unable to speak, causing a sensation that felt like a blackout. “This is it,” I thought, “I’m having a stroke.”

It happened quickly but simultaneously in slow motion. The sensation passed in about a minute without actually leaving me on the floor, and afterward, I was immediately exhausted, in tears, terrified and couldn’t shake the feeling that my limbs weighed a ton.

My talk with the doctor that evening did nothing to ease my mind. After tearful phone calls to my boyfriend and parents, I spent a fitful night trying to decide what to do and also trying to stay awake, irrationally certain that I could stave off a blood clot catastrophe by avoiding unconsciousness. I didn’t know then this would be one of many nights spent in sheer terror over months to come.

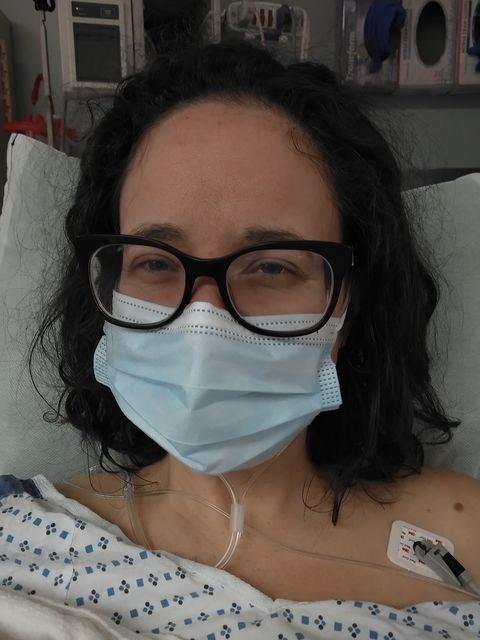

I braved a cab into Manhattan to a hospital around 5 a.m., grimly hoping that the early morning hour would mean fewer patients around me. I was quickly ushered to a bay of ambulatory care cubicles, where I was surprised to find I was the only patient. Wherever COVID-19 was wreaking havoc, it wasn’t where I was being held.

Breathlessly recapping the traumatic episode to the hospital’s doctor, I was quickly wheeled to radiology to have a venous ultrasound to search for a blockage after my blood was tested. Imagine my relief when the doctor reported some good news: There weren’t any blood clots. Then, my heart sank when they told me that my white blood cell count was elevated, hinting at some hidden infection. Could it be COVID-19 already?

The catch-22 in the early days of COVID diagnosis, at least in New York, was that tests were scarce. I couldn’t get one, even with an elevated white blood cell count. I wasn’t coughing or feverish. My only physical symptoms were nervous tension and a slight ringing in my ears. “We’re going to do a chest X-ray,” the doctor explained. “If there’s fluid in your lungs, you can assume you have COVID.”

But the rollercoaster of emotions continued when I heard that my lungs were clear. Medics sent me home with a prescription for antibiotics, to treat whatever non-COVID infection was evidently plaguing me. I left feeling so relieved, hungry, and thankful that this ‘panic attack’ was over. By the end of the day, I felt basically back to normal and ready for a full night’s sleep.

The next morning, feeling refreshed and eager to continue writing, I sat back down at my desk, ready to get back to work. Twenty minutes later, the sensation came rushing back: The sinus pulsing, the thundering in my ears, the terrifying feeling that my life was about to end.

“No!” I cried aloud, willing the rising swell of energy to pass. I jumped up and started staggering around the room. The sensation abated more quickly than the first time, but now, I was downright confused about what to do. I couldn’t very well go to the emergency room again, having gotten a clean bill of health the day before. I sunk into my chair, defeated. What now?

The episodes continued almost daily, and even came for me in my sleep. How could I be having panic attacks if I wasn’t even conscious to have anything to panic about?! I would awake drenched in sweat, unable to fall back asleep for fear that something more was really wrong. Other symptoms started arriving: Constant ear ringing and sinus pressure, pervasive dizziness and cloudiness in my brain, and frequent pinching sensations in my limbs and scalp.

For the next several weeks, determined not to live with this mystery affliction forever, I did everything in my power — which wasn’t much — to either fix or physically troubleshoot what might be wrong with me. I suffered through headaches and took caffeine out of the equation. I started taking a probiotic in case gut health was the culprit. I tried every over-the-counter remedy available for ear-ringing, which mostly just resulted in wet or oily pillowcases. With most medical clinics closed for anything more than extreme cases, for a doctor’s advice I had to rely on telehealth appointments only.

Having nothing other than my report of vague, non-threatening symptoms to work with, my primary care doctor proceeded as though this was simply panic disorder. She prescribed an anti-anxiety medication that did take some of the edge off after an attack, but didn’t stop them from happening. In early April, I spoke to an ear, nose and throat specialist about the sinus pressure and ringing in my ears, who also couldn’t do anything without actually being able to examine me, as his nearest availability was two months out because of COVID closures.

Having already lived with the attacks and mystery symptoms for even just a couple of weeks, I couldn’t even imagine that I would still be experiencing all of this in June.

I was later directed to a cognitive-behavioral therapist who listened as I explained my ongoing symptoms and episodes. She used hypnosis to try to help me find a place of peace. And yet still, I couldn’t shake these attacks. Then I tried meditation. I tried tapping. I bought a pulse oximeter so I could literally prove to myself that oxygen was still reaching my heart while an attack was happening.

All of these little remedies were prescribed assuming that I was experiencing panic disorder. In my heart, I knew it was something more than that. I have never been prone to hypochondria, but another factor of living in an unemployed, COVID universe is that I had nothing but time to over-examine all of my symptoms. I knew something was wrong.

My therapist also recommended that I go on long walks. I was trying to walk daily, but the more the attacks occurred, the more fearful I became of being too far away from my apartment. There were days that I would just be circling my immediate block, when my legs would become heavy and uncooperative. Some of those walks barely lasted five minutes.

On April 30, during a daily check-in phone call with a close friend, a sense of bodily heaviness overtook me so strongly, it almost felt like paralysis. “I think I have to go back to the ER,” I told her tearfully, feeling desperate for someone to examine me in person again.

Back again at the same emergency room, the staff ran all of the same diagnostic tests, though this time I was also able to get tested for COVID. Again, I was sent home with an assurance that nothing was wrong with me, and that they would call with my COVID result as soon as they had it. As I awaited that call, I almost wished for the unthinkable: I wanted it to be positive. It was a testament to how badly I wanted a reason to explain my symptoms, that I was more than willing to let that reason be a deadly disease ravaging the world.

The test was negative. COVID-19 was not to blame.

On June 9, finally able to see a non-emergency doctor in person, I blitzed through four different appointments on the same day. Midtown Manhattan was a ghost town when I went to the clinic, just two blocks from the busy restaurant where I used to work; yet still I felt buoyant being there. Finally, I thought, this is the day when I’ll get some answers.

My gynecologist did a blood test to see if I had begun pre-menopause. At 46 years old, it was early, but not out of the question — maybe the episodes were just extreme hot flashes? Then, a cardiologist did an EKG to check for irregularities in my heart. An allergist pricked my arms to determine if I’d developed a late-in-life allergy to the spring pollen. The ENT doctor I had previously spoken to on the phone had a look around my sinus cavities with a camera.

And I was infuriated when all these tests revealed… nothing. Everything seemed to be in working order. I had perfect hearing; I never had an allergy, and still didn’t.

“What would you do if you were me?” I asked the ENT doctor, in tears, after all my fruitless efforts. He referred me to a neurologist. Even though I had been okay with the idea of a positive COVID test to explain this malaise, the possibility that something was seriously wrong with my brain was not one I was willing to wish for.

On June 15, I had a telehealth visit with Caroline Miranda, M.D., a specialist in neurophysiology at Columbia University. Nearly three months since my first episode, I numbly walked her through all of my attacks, symptoms, hospital visits, appointments and tests.

“What you’re experiencing is something called Post Viral Syndrome (PVS),” she said confidently, without missing a beat. My brain tried to catch up with the relief that washed over me. There was a name for what was wrong with me, and it wasn’t just panic disorder or another form of anxiety.

She went on to explain that PVS is a result of your nervous system getting caught in the crossfire of your immune system at work. The episodes and symptoms I was experiencing were all just a result of neurological misfirings, caused by the body’s response to a virus. Known formally as myalgic encephalomyelitis, and previously as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, the term Post Viral Syndrome was developed by experts to include a wide array of potentially long-lasting symptoms that can arise while the immune system is working to fight infection.

“Post Viral Syndrome is an umbrella term physicians use for the myriad complications one can experience following a viral infection,” Dr. Miranda explained to me recently over email. “It is our understanding that inflammation used to fight the infection can negatively impact various parts of the human system. In neurology, for example, sometimes we see the peripheral nerves affected, resulting in peripheral neuropathy which can cause symptoms like tingling, pain and numbness.”

The phantom pinching sensations were the most compelling part of my experience, revealing that my nervous system was indeed affected. The fact that I’d also had an elevated white blood cell count during my very first ER visit also correlated with her diagnosis.

She prescribed a nerve pain medication that evened me out in a matter of weeks. By early July, almost four months after my first episode, the attacks finally stopped for good, and I was able to take walks for longer than 10 minutes and further than one block from my apartment.

In the end, I’ll never know if COVID triggered my bout with Post Viral Syndrome, or if it was another virus entirely — the timing of my first hospital visit ensured it will always be a mystery. I could have had COVID-19 in February 2020 or even earlier, and antibodies wouldn’t be lingering to detect later that spring when I took my first antibodies test.

But a common cold or flu could just as easily have been to blame, Dr. Miranda explained. I felt validated all the same when this seemingly rare condition entered the pandemic lexicon later that summer, as COVID long-haulers started to crop up. In a conversation dated July 17 between Dr. Fauci himself and Dr. Eric Topol, Editor-in-Chief of Medscape, Dr. Fauci referenced my condition: “Even after you clear the virus, there are post-viral symptoms… And it’s extraordinary how many people have a post-viral syndrome that’s very strikingly similar to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome.”

It’s been well over a year since I’ve experienced any kind of attack, but it turns out that Post Viral Syndrome is often viewed as the prompting trigger behind symptoms that many have since called “Long COVID.”

I’m grateful to have finally stumbled upon the right doctor to help me move past the debilitating condition, and I have hope that those who persist past Long COVID symptoms may find the same relief as the phenomena is becoming more understood by healthcare providers at large.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io